Introduction

Ideology has been a central concept muddled by diverse uses in the study of politics. Philip Converse perhaps provided a classical operationalization of ideology– a “belief system” representing the configuration of attitudes and ideas. In China, where the state could dominate the private sphere, comprehending the ideological landscape is crucial to capture Chinese politics and even Chinese society’s every aspect.

Data

Source

The study employs the zuobiao survey (Chinese Political Compass) that contains 50 questions about a wide array of critical issues in China. Peking University’s graduate students and researchers designed the survey, the same source used in Pan and Xu’s study in 2018.

Each question in the survey is on a four-point Likert scale– “strongly disagree (1),” “disagree (2),” “agree (3),” and “strongly agree (4).” Q5 measures people’s perception of replicating western-style freedom in China, and Q3 sets up a hypothetical yet usual situation in China to let people make the judgment. As the figure above displays, around 55% of respondents disagree with the statement that indiscriminately imitating western-style freedom of speech will lead to social disorder in China. In comparison, 45% of respondents agree or strongly agree. Despite the increasing risks of social unrest, 47% of respondents support transparency under the crisis, and 53% disagree with the statement.

Q5 and Q3 reveal that respondents favor information transparency under the crisis, a key component of democratic accountability, yet reject the idea of imitating western-style freedom. Although the term “indiscriminate” in Q5 leads respondents to disagree with the statement, the underlying preferences should be consistent, suggesting that people who support information transparency should also promote free speech or vice versa, despite the cost of bringing social disorder.

Other than the survey data, the study obtains the data from Zhihu by a scraper. Zhihu is a Chinese version of Quora and attracts millions of users to share opinions on a specific question. The data is from a specific question on Zhihu about perceiving nationalism. That question has more than 500 answers with more than 6,700 comments and 14,800 votes.

Methods

Principle Component Analysis (PCA)

50 questions on ideology can make one confused about which one matters. As a frequently-used dimension-reduction technique, PCA can remove the noise by reducing a large number of features to a few principal components (PCs). Rather than the random guess, Kaiser’s rule, which is to retain components whose eigenvalue is greater than 1, can help decide the best number of components. The optimal number of PCs should be 10. Meanwhile, 10 PCs merely explain 46.7% of the total variance, and we lose more than half of the information.

Synthetic Index Approach

The study manually creates synthetic indices based on questions revolving around the same theme. Building on previous studies, the survey questions are classified into seven themes: Democracy, Freedom, Market, Socialism, Globalization, Traditionalism, and Nationalism. Each question is labeled as +1 to represent the support and -1 to represent the non-support of one specific theme. Each index is a combination of such values. The mean of each index is 0.128 for Democracy, -0.525 for Freedom, -0.506 for Market, 1,556 for Socialism, -1.057 for Globalization, 0.755 for Traditionalism, and 1.007 for Nationalism. These metrics portray a fictitious average respondent in China: one slightly favors democracy, looks slightly conservative, believes socialism and traditional Chinese culture, prioritizes nationalism, and is suspicious of the free market and economic globalization.

To better make the inferences, here employs the logistic regression under $L$1-regularization for feature selections. The model is displayed as below:

\[\mbox{Pr}(Q=1|X=x)=\frac{e^{\beta_0+\beta_kx}}{1+e^{\beta_0+\beta_kx}}\] \[\min_{(\beta_0, \beta_k) \in \mathbb{R}^{p+1}} -\left[\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N y_i \cdot (\beta_0 + \beta_kx_i) - \log (1+e^{(\beta_0+\beta_kx_i)})\right] + \lambda\sum_{j=1}^p{|\beta_j}| s\]where $k$ $\in$ ${Index, Demographic}$ and $\beta_k$ represents the coefficient of $k$’th variable of the set, and we are trying to find the $\beta_0$ and $\beta_k$ that minimizes the error under the $L$-1 regularization.

As the below left figure reveals, one that leans towards democracy, freedom, and the market is© more likely to support information transparency under the crisis, while the supporter of nationalism or/and traditionalism is less likely to agree. If one inclines to the socialist ideology, he or she may also agree. Freedom is the main force driving information transparency, and Nationalism is the primary opposite factor among all the indices. The result is in line with our intuition that freedom and government domination, the usual practice of withholding information, are incompatible. Besides being male, positively associated with information transparency, the remaining demographic variables do not display a clear pattern.

In light of the above figure, we can find that one supports democracy, freedom, and the market tends to disagree. One who follows traditionalism or nationalism also embraces the idea. Interestingly, respondents with a college education or above than those who fail to attend high school are more likely to agree with the statement. A possible explanation for this is that well-educated people in China may have a deeper understanding and see the flaws of freedom than the laypeople. Thus they tend to reject the idea of indiscriminate imitation. The same explanation could also apply to individuals whose income is between 150k and 300k. As for living in southwest China and being male, it is hard to figure out the exact reasons. We may attribute that phenomenon to Lasso’s arbitrary feature selections.

What is Chinese talking about when they talk about nationalism?

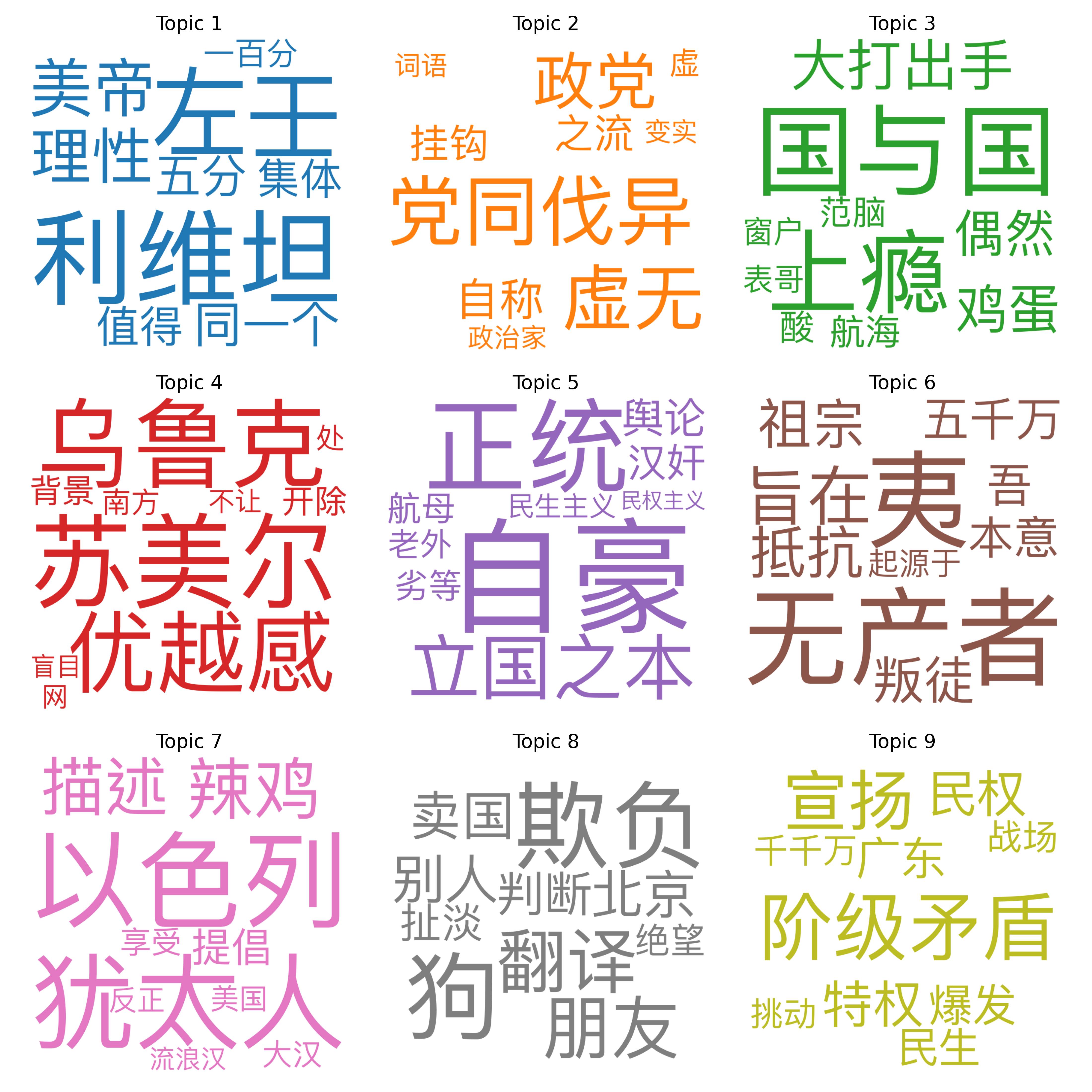

Here employs the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to extract topics of a Zhihu (the Chinese version of Quora) question about “how to perceive nationalism.” Perplexity and coherence scores are measures to evaluate the model’s performance. The higher the coherence score, the more consistent the topic would be. Generally, the perplexity score would decrease along with the number of topics. The above figure displays that 12 topics seem to make the most sense. Then, the cloud of top words could help us understand each topic’s theme.

The above figure displays 9 out of 12 topics’ word clouds:

- Topic 1 contains 美帝 (American Imperialism), 左 (the leftist), 利维坦 (Leviathan), and 五分 (a pejorative term for a supporter of the Chinese government without thinking);

- Topic 2 focuses on politicians and parties, including 政客(politicians), 政党 (political parties), and 党同伐异 (factionalism);

- Topic 3 is primarily about 国与国 (state-to-state);

- Topic 4 involves 乌鲁克 (Uruk) and 苏美尔 (Sumerian);

- Topic 5 and 9 are similar and encompass Sun Yat-sen’s 民权主义 (Government by the People) and 民生主义 (People’s welfare/livelihood). Topic 5 exclusively contains 正统 (orthodoxy), 立国之本 (the state’s foundation), 自豪 (proud), and汉奸 (a pejorative term for a traitor to the Han Chinese), while topic 9 leans towards 特权 (privilege) and 阶级矛盾 (class conflict);

- Topic 6 sheds light on 祖宗 (ancestors) and 夷 (barbarian/foreigners) on the one side, and 无产者 (Proletariat) on the other;

- Topic 7 is about 犹太人 (Jewish) and 以色利 (Israel), both of which are closely related to Zionism;

- Topic 8 is similar to topic 5 in terms of 卖国 and 狗, and both are traitors’ different expressions in Chinese.

Discussion

Attitudes towards democracy, market, and nationalism essentially constitute China’s ideological landscape. In short, when Chinese talk about nationalism, they are reminding themselves of the orthodoxy Han (Han, proud, and ), in contempt of the traitor (in the Japanese invasion and now), and inheriting the Sun Yat-sen’s snd socialist legacy. Moreover, Cantoni et al.’s study sheds light on how mandatory high school politics curricula might shape students’ ideology. They find that the new curriculum introduced in 2005 has successfully changed students’ attitudes in the Chinese government’s direction. Students exposed to the new curriculum generally see China as more democratic and express skepticism towards the unconstrained democracy and free markets.

More than 80% of respondents have received a college degree or above, so we may need to realize the implicit selection bias for those finishing the zuobiao survey. The “fictitious average respondent” could be far more liberal, market-oriented, and less nationalist than it could be. Given the political constraints in China, it is more challenging to acquire the data. Meanwhile, making sense of China’s ideological landscape and dynamics are indispensable for anyone attempting to understand China.